Driven Grouse Shooting – Implications for Upland Birds

The subject of driven grouse shooting is a controversial one. In current times the shooting fraternity finds itself besieged with calls for an all out ban on driven grouse shooting and barely a day passes with the topic not broached on social media.

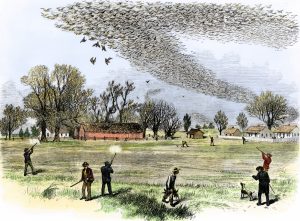

Image: Sacha Elliott

Image: Sacha Elliott Recently, the British Association for Shooting and Conservation (BASC) released a statement claiming that shooting and conservation are one in the same and that without associated management for shooting purposes many upland species would suffer in the UK. This announcement has understandably been met with a mixed reception by the ecological community and has peaked my interest of late.

The subject of driven grouse shooting is a controversial one. In current times the shooting fraternity finds itself besieged with calls for an all out ban on driven grouse shooting and barely a day passes with the topic not broached on social media. Many frustrated conservationists hold the practice single handedly responsible for the demise of protected raptors across vast swaths of the UK while animal rights activists condemn the wide scale predator control that takes place as inhumane. Conversely, shooters argue that grouse moors in fact bolster conservation with management and legal predator control greatly benefiting many upland species. Driven grouse shooting is perhaps the most topical issue in British conservation today and in recent times and has sparked unbridled animosity between alternate factions with high profile conservationists such as Mark Avery and Chris Packham going as far as to call from an end to the practice all together.

It is necessary to leave sentiment behind when referring to driven grouse shooting, to access matter of factly whether or not Grouse moors do indeed benefit conservation. With evidence in existence both in favour and against the practice there is certainly room for debate. Before delving headlong into the maelstrom it is necessary to break the topic up into more manageable chunks. As such, for this post at least, I will focus solely on the avian implications of driven grouse shooting, absent personal opinion and compiled from the existing knowledge base.

Foregoing charismatic, headline grabbing raptors for the time being, the other species often most associated with grouse moors are wading birds. Many of Britain’s breeding waders favour Calluna dominated upland habitats and many such Lapwing, Golden Plover, Curlew and Snipe can be found breeding on management moors. According to the shooting community these species are those that benefit most from predator control and habitat management in upland areas. Perhaps the most concise information base on the subject comes from the RSPB (2012) and the research paper entitled: “The costs and benefits of grouse moor management to biodiversity and aspects of the wider environment: a review”. Here information is given for many wading bird species absent any form of bias. Both Curlew and Golden Plover benefit directly from moorland management through the maintenance of prime breeding habitat. The report states for both species that “Benefits from management produce higher densities on grouse moors.” Lapwing likewise stand to benefit with the RSPB acknowledging that “the predator control regimes associated with grouse moors may be important in maintaining (or slowing declines of) populations of several species that are declining nationally (notably black grouse Tetrao tetrix, lapwing Vanellus vanellus and curlew Numenius arquata).” Conversely however the RSPB stress that there is little evidence suggesting that other upland breeding waders stand to benefit directly from grouse moors, among these; Dunlin, Snipe and Greenshank.

Strengthening the previous comments, a more recent study by Warren & Baines (2014) focused on the Berwyn Special Area for Conservation (SAC) in Wales found that once grouse centric management creased in the study area that breeding waders showed dramatic declines, writing that: “By the late 1990s driven grouse shooting had ceased. Between initial surveys in 1983-5 and a further survey in 2002, lapwing were lost, golden plover declined by 90% and curlew by 79%.” Further studies highlighted by BASC also show a positive correlation between grouse moors and wader numbers with notable examples including those of Aebischer et al, (2010) and Baines et al (2008). The latter concluding that “Golden Plover and Curlew were approximately two to three times more abundant where moorland was managed for Grouse and that Lapwing were virtually lost after gamekeeping ceased.” Tharme et al (2001) also state that breeding densities of Lapwing and Golden plover were “five times higher” on sites managed for shooting purposes. It is therefore, in my opinion, safe to conclude that the shooting of grouse does indeed benefit at least some of Britain’s wading birds, many of which are now red and amber listed by the RSPB due to recent declines and pose considerable concern in modern times.

When it comes to upland passerines available data is a lot less concise than it is for waders though with a little determination some information can be found. The Meadow Pipit, one of the most numerous bird species in the British uplands has been shown to be negatively affected by rotational miniburn that takes place on Grouse moors. The RSPB (2012) concluding that although nesting success is likely increased by predator control that densities are generally lower on sites managed for shooting purposes. Unlike the Meadow Pipit, many upland passerines appear relatively un-phased by management practices however, with breeding densities remaining consistent across both managed and un-managed sites. Among these Whinchat, Wheatear and Skylark (RSPB, 2012). Aside from this the RSPB (2012) also state that little evidence exists to aptly assess the implications of moorland management on other species such as Twite and Ring Ouzel.

Contrasting with the above, there are however those that put forth findings that suggest a positive relationship between moorland management and upland passerines. Baines et al (2008) write that: “Skylark were approximately two to three times more abundant when moorland was managed for grouse than when it was not” while the RSPB (2012) state that Skylark may well be “more abundant” in areas where raptor numbers have been reduced through illegal persecution. Warren & Baines, (2014) also highlight a positive association between moorland management and Ring Ouzel abundance on their Welsh study site with “Ring Ouzel declining by 80%” once gamekeeping in the area came to an end. These conflicting data-sets highlight the need for an increase in research into passerines on grouse moors and until then it is difficult to make a decision as to whether these species benefit or suffer as a result of grouse focused management. The likelihood is however that as with waders, there will of course be both winners and losers.

Referring briefly to gamebirds and as one would expect, Red Grouse are abundant on grouse moors. The key is in the name really. Red Grouse densities are maintained at an artificial level for economic purposes and in some cases managed sites hold twice the number of Red Grouse as opposed to other, more natural, sites (Tharme et al, 2001). Much more important however, at least from a conservation standpoint is the effect of moorland management on numbers of Black Grouse, a species of considerable conservation concern in the UK. The RSPB conclude that in situations where legal predator

control takes place that this species seeks to benefit with “several studies” highlighting increased levels of breeding success. Rotational miniburn may also benefit this species by maintaining the young nutritious shoots preferred for feeding though equally, the process may also limit breeding habitat preventing the growth of scrub and woodland.

Finally we come to the perhaps the most topical grouping. It is widely known that many species of raptor are illegally persecuted on moorland sites across the UK. Species such as Buzzard, Red Kite, Golden Eagle and of course Hen Harrier all fall victim to the practice and it is certain that where such actions take place that the conservation status of these species is negatively affected. One need only look at the Hen Harriers virtual extinction from England to see that this is horribly apparent. The RSPB (2012) write that: Several species of predatory bird breeding on moorlands are subject to illegal killing, nest destruction and disturbance because of their documented or reputed impact in reducing the shootable surplus of red grouse (Thirgood et al. 2000b, Park et al. 2008). Such activity has the potential to limit population densities and restrict the geographical range of these species, and when in the past it was more widespread and indiscriminate it has been responsible for reducing populations of some species to low levels and even extinction in Britain and Ireland (Newton 1979).

Absent persecution however the implications of grouse moor management on birds of prey would be distinctly different. Grouse moors maintain suitable breeding habitat for a number of species including Short-Eared Owl, Hen Harrier and Merlin (RSPB, 2012) and benefit other species such as Golden Eagle and Peregrine through increased prey availability. Some studies, notably that of Baines et al (2008) in fact highlight a direct correlation between grouse moor management and raptor numbers, in this case Hen Harriers. Warren & Baines (2014) also noted a 49% decrease in Harrier numbers in the Berwyn Special Area for Conservation once gamekeeping operations in the area subsided. In my opinion at least, it is safe to assume that should illegal persecution of birds of prey be curbed that management moorland sites could indeed benefit a number of raptor species through the creation of suitable breeding habitat and an increase in natural prey sources. Alas the likelihood of this happening anytime soon however remains rather slim.

The above article comprises information derived from a number of sources though I freely admit that it relied heavily on the review collated by the RSPB (2012). This can be found online and offers a broad assessment of moorland management and the resulting implications. Trying my utmost to keep sentiment and personal opinions out of it, it is clear to me that the management of moorland sites for Grouse does indeed reap rewards. Notably for declining wading birds such as Lapwing and Golden Plover. It may also benefit other notable species such as Black Grouse, Skylark and Hen Harrier. The latter a distinct possibility should illegal persecution be tackled. There is however a huge gap in the literature when it comes to many species and even the RSPB freely admit that a lot more research is needed before making an overall decision in regards to the avian implications of grouse moor management. This is summed up perfectly here: Despite the fact that the evidence base for assessing the effects of grouse moor management is greater for birds than for other taxa, for some predatory species (e.g. short-eared owls) and waders (e.g. dunlin), and for most of the moorland passerines, the overall impact of grouse moor management on their populations is poorly understood. This includes rapidly declining species, such as ring ouzel. More widely, it seems likely that grouse moor managementgenerally limits overall bird species diversity by restricting scrub and woodland habitats (Thompson et al. 1997), and it would be valuable to establish the extent to which such habitats could be developed on moorland edge areas, without compromising the status of moorland bird species of conservation importance. Research on the importance of other managements that may be associated with grouse moors (e.g. drain blocking) is also warranted. I for one look forward to further research into this controversial but undeniable interesting topic.

One Comment

A well-written and unbiased piece, something of a rarity on this particular subject.